Profile: Polish water sector

-

Editorial Team

Editorial Team

Share article:

Water News Europe is providing profiles of the water sector in different Member States. The Republic of Poland has been an EU member state since 1 May 2004. The currency is the Polish zloty (ZL), however, the country is committed to adopting the euro (EUR) once it fulfils the necessary conditions. Part of these conditions is complying with European Directives, like the water directives.

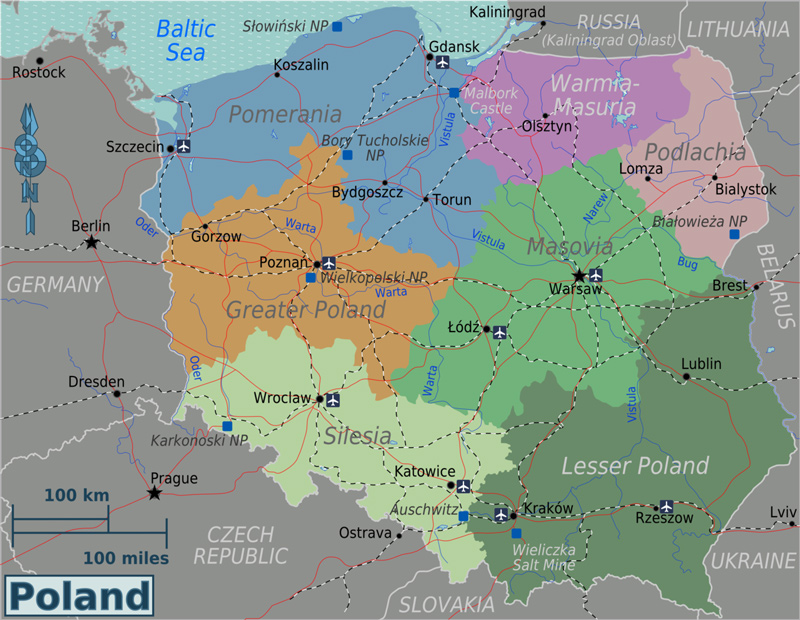

Geography

The country borders Germany to the west, the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Ukraine and Belarus to the east, and Lithuania and the Russian province of Kaliningrad Oblast to the northeast. To the north, Poland is bordered by the Baltic Sea. The climate is oceanic in the northwest and becomes gradually warmer and continental towards the south-east. Summers are generally warm, with average temperatures between 18 and 30 °C depending on the region. Winters are rather cold, with average temperatures around 3 °C in the northwest and -6 °C in the northeast. Precipitation falls throughout the year, although, especially in the east, winter is drier than summer.

The country has a dense water network with the longest rivers being the Vistula at 1047 km long. The Odra River which forms part of Poland’s western border is 854 km long; its tributary, the Warta is 808 km long; and the Bug, a tributary of the Vistula, is 772 km long. The Polish Baltic coast is approximately 770 km long and extends from Świnoujście on the islands of Usedom and Wolin in the west to Krynica Morska on the Vistula Spit (lagoon) in the east.

Polish waterways

Poland is investing billions in international waterways. Connecting the Baltic Sea with the Black sea will be a major achievement for international shipping. The navigability of many Polish rivers is meant to improve European water connections. “A new canal that will cut across the Vistula Spit, allowing Polish ships to reach the Baltic sea without having to pass through Russian-controlled water, will likely be opened this year,” announced Poland’s deputy infrastructure minister in February 2022 on the Polish news platform tvpworld.com

Water Stress

With almost ten thousand closed bodies of water covering more than one hectare (2.47 acres) each, Poland has one of the highest numbers of lakes in the world. However, despite this, the water resources in Poland are very scarce, ranking in the last place in the EU (with 1,600 m³ per inhabitant); 97% of this comes from precipitation. However, much of the rainfall water is lost because it is not stored and goes via rivers to the Baltic sea.

Polish Water and wastewater

In 2018 the length of the water and sewage network in Poland was nearly 470,000 km. Most – 307,700 km – are waterworks, although the dynamics of growth are greater for the sewage system. According to the latest data from the Central Statistical Office (GUS), in 2018 the length of the sewage network in Poland increased by over 3900 km (2.5%) compared to 2017. Most sections (59%) are still in rural areas. There, the increase in the length of the network is greater (by 1.3%) than in cities – in the previous year it amounted to 3% (2,800 km of canals were added, while in urban areas – 1,100 km were added).

The greatest increase in the network was recorded in the following voivodeships (the highest-level administrative division of Poland): Lubelskie – 3.8%, Mazowieckie – 3.6%, and Wielkopolskie – 3.2%. The fewest new sections of the sewage system were built in Lubuskie – 0.7% and in the western part of Pomerania – where the length of the network increased here by only 0.1%. The statistics are slightly different in the case of the density of the sewage network. The largest was recorded in Silesia – 135 km per 100 km² and Małopolska – 107 km per 100 km², the smallest in Podlasie -18 km per 100 km² and in the Lublin region – 27 km per 100 km².

According to the information provided by the State Water Holding Polish Waters, at the end of 2016, there were 1,658 biological wastewater treatment plants operating in Polish agglomerations, of which 601 with increased removal of biogenic compounds. Moreover, the fifth update of the National Program of Municipal Sewage Treatment (VAKPOŚK) shows that 1,468 treatment plants (88.5% of all facilities), including 561 facilities with increased removal of biogenic compounds, met the requirements for the quality of treated sewage.

The five largest wastewater treatment plants in Poland are:

- Czajka Wastewater Treatment Plant – Warsaw: capacity 515,000 m³ / day,

- Group Sewage Treatment Plant of the Łódź Agglomeration (GOŚ-ŁAM): capacity 332,000 m³ / day,

- Sewage Treatment Plant Płaszów – Kraków: capacity 328,000 m³ / day,

- Central Sewage Treatment Plant in Koziegłowy – Poznań: capacity 260,000 m³ / day,

- Janówek – Wrocław Wastewater Treatment Plant: capacity 170,000 m³ / day.

Ministry of Climate and Environment

The Ministry of Environment (MoE) is responsible for adopting the National Environmental Policy, overseeing several institutions with relevance for water issues, including the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (Główny Inspektorat Ochrony Środowiska), which monitors the state of the environment including the quality of water, and the National Fund of Environmental Protection and Water Management (Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej) which provides funding for environmental investments, including those in the Polish water sector. The Ministry of Maritime Economy and Inland Navigation (Ministerstwo Gospodarki Morskiej i Żeglugi Śródlądowej) deals with maritime issues, fishing and inland navigation.

The National Water Management Authority (NWMA)

The President of the NWMA carries out his duties with the support of the NWMA which was established by the Water Act of 18 July 2001 yet only came into being on 1 July 2006 after the Prime Minister had conferred the statute on 27 June 2006.

The statutory duty of the Regional Water Management Authority (RWMA) is to manage waters in accordance with the principle of sustainable development, in particular to shape, protect and manage water resources. To achieve these goals, it serves, among others, to control water management, in particular, compliance with the obligations imposed by the water permit on water users.

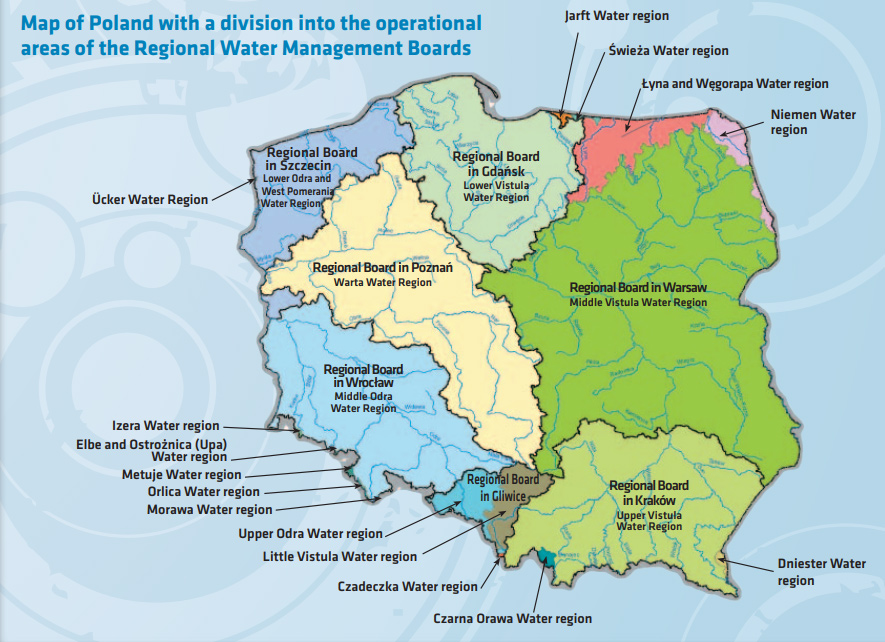

The Regional Water Management Boards (RWMB)

There are seven RWMBs, which are responsible for water management in their regions, including identification of significant pressures and assessment of their impact on the status of surface water and groundwater, along with, for example, economic and water use analysis. Their Directors are subordinated to the President of the NWMA.

Gdańsk

The RWMB in Gdańsk is responsible for the Lower Vistula water region and covers the Vistula basin downstream of Włocławek to its estuary into the Baltic Sea, as well as the basins of other rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea west of the Vistula estuary, up to and including the Słupia, and east of the Vistula estuary, up to and including the Pasłęk. The length of the Vistula section within the Lower Vistula water region is 260 km, while the total length of the hydrographic network of the water region is approximately 2,120.74 km. The main right-bank tributaries of the Lower Vistula section are the: Drwęca, Osa, Mień and Fryba. The largest tributaries in the region are the: Brda , Wda, Wierzyca, Motława, Zielona Struga and Tążyna.

Gliwice

The RWMB in Gliwice is located in the southern part of Poland and covers an area of approximately 8,387 km², which is approximately 2.5% of the country. It covers about 49% of the Śląskie Voivodeship, approximately 11% of the Opolskie Voivodeship and 5% of the Małopolskie Voivodeship. Within this RWMB there are 37 administrative units at the poviat level, including 18 municipal poviats. It administers the following inland waterways: the Odra River (km 51.2 – 98.6), the Gliwice Canal (km 0,0 – 41,2), and the Kędzierzyn Canal (km 0.0 – 5.6).

Krakow

The RWMB in Krakow manages the upper part of Vistula Water Region including the San, Dunajec, Skawa, Sola, and Nida rivers.

Poznan

The RWMB in Poznan covers the Warta Water Region; the entire basin area is 54.500 m², about 17.4% of the area of Poland. The Warta River is 808.2 km long and is the largest right tributary of the Odra River. It is longer than the part of the Odra above the cross-section of the mouth of the Warta. The south and west of the Warta catchment area borders the Odra river basin (of which it is a part), and it borders the Vistula basin to the east.

The sources of the Warta are located in the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland near Zawiercie. The Warta flows into the Odra River in the vicinity of Kostrzyn. The larger rivers flowing in the Warta Water Region are the: Noteć, Prosna, Drawa, Obręa Gwda, Ner, and Wełna. The river network is well developed and there are also numerous lakes, with their main clusters in three lake districts: Wielkopolskie, Lubuskie, and Zachodniopomorskie.

Szczecin

The RWMB in Szczecin covers two water regions: the Lower Odra and the Western Pomeranian, and the Ücker. The largest river in the Lower Odra and Western Pomeranian water region is the Odra (219.5 km within the RWMB in Szczecin – from the Nysa Łużycka to the Roztoka Odrzańska estuaries). It is also the largest and richest watercourse in this water region.

Wroclaw

The RWMB in Wroclaw is responsible for the management of the Middle Odra River Region that also includes the small rivers Nysa Klodzka, Kaczawa, Bobr, Barycz, Mala Panew, and Nysa Luzycka.

Warsaw

The RWMB in Warsaw manages an area of 111,000 km² (about one third of the territory of Poland). The region includes a part of the Vistula river basin (the region of the middle Vistula) and parts of the water regions of Jarft, Świeża, Łyna, Węgorapa and Niemen. The RWMA in Warsaw also manages 29 rivers, which are 3,000 km long in total.

The most significant facilities administered by the RWMA in Warsaw are the Dębe, Włocławek, Brody Iłżeckie, Wióry, Sulejów reservoirs, and the Żerański and Augustowski canals, encompassing facilities in the area of the Great Masurian Lakes.

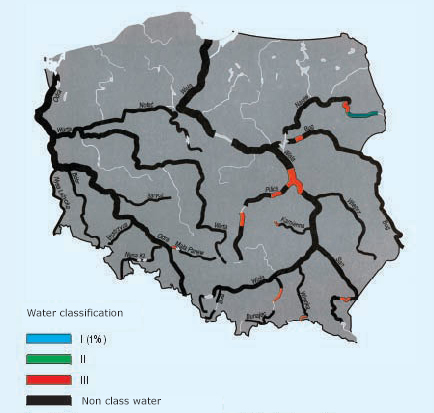

Sources for Drinking Water Production

In Poland drinking water is mainly (70%) from groundwater. In eleven voivodeships, as of 2015, over 75% of water came from underground. Only two voivodeships are dominated by surface water among others in the Silesian Voivodeship. There are approximately 1,300,000 km³ of groundwater. The physical, chemical and biological cleanliness of surface water in Poland determines its purity classification. The best sources belong to class I and, in accordance with the Regulation of the Minister of the Environment (Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland No. 422 of 1987, item 248), it is only from such waters that waterworks can produce water intended for drinking. The problem is that there are no such waters in Poland (only 2% in 2002). Due to the lack of better raw material, drinking water in Poland is made of class III water (approx. 30%) and non-class water (approx. 60%), i.e., sewage. According to the research of the health authorities, over 80% of wells in Poland contain water that is not suitable for drinking.

Polish water sector organisations

Polish Association of Natural Bathing Waters

The founding members of the Polish Association of Natural Bathing Waters (PSNWK) are fond of natural water purification in swimming ponds and reservoirs. The PSNWK was created as a result of observation of the activities of the European Industry of Designers and Builders of Swimming Ponds. The desire to transfer many years of experience and develop quality standards of colleagues from elsewhere in Europe gave rise to an association modeled on proven solutions.

International Water Association (IWA) Poland

The National Board of the IWA Polska represents Polish interests and experience in the water and sewage industry at the forum of the IWA. The IWA is a non-profit organization with over 10,000 members from 130 countries around the world. The IWA Polska branch was established in 2015/2016 by Jakub Drewnowski and Jacek Mąkini, the former vice-rector for cooperation and innovation at the Gdańsk University of Technology. Makini was appointed chairman of the IWA Polska for the years 2016-2019. Members of the National Committee of IWA Polska are long-term members of the IWA, who represent both the scientific community and the world of the water and wastewater industry in the international arena. IWA Polska brings people together to share knowledge, experience, and know-how about the most pressing water challenges and innovative solutions as well as contributing to water science and technology by stimulating leading-edge science and innovations and helping scientists connect to their peers, publish their latest findings and help others learn with them.

Polish Water Companies

MATPOL

MATPOL is located in Szczecin and has provided services related to underwater works and hydraulic engineering since 1998. The main profile of the company’s activity is services related to hydraulic engineering and underwater works. The company assesses the technical condition of hydrotechnical structures, installs fenders on quays, and carries out inspections of underwater hydrotechnical structures and seals them.

WOD-INŻ

WOD-INŻ systematically participates in the modernization of existing sewage and water supply pumping stations and the construction of new ones. WOD-INŻ provides services in the field of overcoming terrain obstacles using the pneumatic jacking method and controlled drilling in the diameter range from 100 mm to 1200 mm.

Jobs and education

According to the latest statistics (2017) the number of people working in the Polish water sector is 131,502.

Water education is provided by several universities and institutes:

- Water management at the Nadnoteckie Institute of Adam Mickiewicz University in Piła

- Executive MBA for The Water Pipe Industry at WSB Academy in Dąbrowa Górnicza

- Alternative Fuels and Energy Use of Waste at Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice

Polish water Legislation

The Polish Water Law Act intends primarily to achieve full implementation of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) (2000/60/EC). The Water Act is of major importance to the transposition process of the Framework Directive, and regulates the management of water resources in line with the principle of sustainable development, especially in the field of the protection of water bodies, the use of water resources and their management.

Poland and Bathing water quality

According to the Bathing Water Directive report from 2020, the bathing water quality has changed slightly. The percentage of ‘excellent’ water quality fluctuated for the period 2017-2020. The percentage of ‘good’ slightly increased for the same period (from 18 to 24). ‘Sufficient’ increased (from 11 to 16). Poor improved (from 2 to 0). ‘Not classified’ has increased drastically (from 19 to 75).

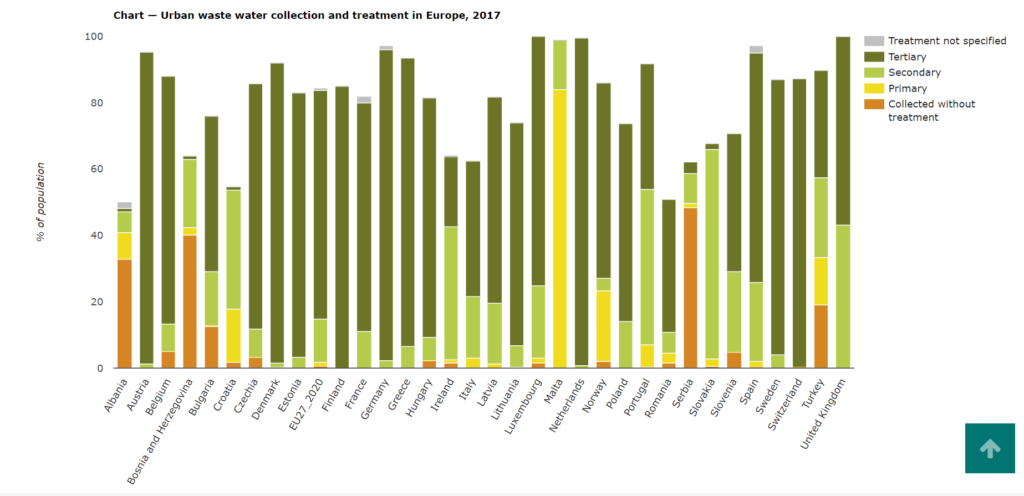

Poland and Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD)

The EU UWWTD sets out a time plan for the construction of infrastructure for collecting and treating waste water in urban areas. In general, waste water must be subject to biological treatment (secondary treatment), which removes a very high proportion of organic pollution, bacteria and viruses. To reduce the risk of algal blooms, further removal of nitrogen and/or phosphorus is required in larger urban areas that are connected to sensitive water bodies.

According to the statistics of the European Environment Agency for 2017, 60% of the water in Poland had been under tertiary treatment, mainly to reduce nutrients, and less than 1% of the water that had been collected from sewage had not been treated before discharge. In 2018, Poland counted 1553 agglomerations generating ≥ 2,000 p.e. each. For the 1553 agglomerations, there are 1718 urban waste water treatment plants, with a total design capacity of 52,584,000 p.e., of which: nine are active but not connected to the collecting system, 1096 are equipped with technology only for primary and secondary treatment, and 613 are equipped with technology for more stringent treatment.

Waste water should normally be directed to a waste water treatment plant before being discharged. However, in Poland, over 1,000 agglomerations do not have a collecting system for their municipal waste water, meaning that it is being directly discharged into rivers, seas or lakes without treatment. In addition, in 415 agglomerations, where wastewaters are being discharged in sensitive areas, Poland has not ensured that those waters are subject to more stringent treatment as required by the Directive.

Poland and the Floods Directive

The Floods Directive requires each Member State to assess its territory for significant risk from flooding, to map the flood risk extent, identify the potential adverse consequences of future floods for human health, the environment, cultural heritage and economic activity in these areas, and to take adequate and coordinated measures to reduce this flood risk.

By the end of 2011, Member States were required to prepare Preliminary Flood Risk Assessments (PFRAs) to identify the river basins and coastal areas at risk of flooding (Areas of Potential Significant Flood Risk – APSFR). By the end of 2013, Flood Hazard and Risk Maps (FHRMs) were to be drawn up for such areas. On this basis, Member States were to prepare Flood Risk Management Plans (FRMPs) by the end of 2015.

Poland has prepared three FRMPs for the Vistula, Odra, and Pregolya. These three Units of Management (UoMs) cover about 99.5 % of the country’s territory. The prior assessment of Poland’s APSFR found that fluvial and seawater flooding was significant.

The 2015 FHRM assessment identified the following area for further development for Poland:

- Maps for about 70 % of potentially significant flood risk areas in Poland still have to be produced. The current maps seem to cover areas around major rivers.

- No APSFRs were reported in PL1000, PL3000, PL4000, and PL6700. Poland has subsequently indicated this was because there were no data on historical flooding, so these areas were not considered to be at risk of future flooding. It was not clear if possible climate change and future socio-economic scenarios were considered.

- None of these areas for further development have been explicitly addressed in the time period between the publication of the FHRMs and the assessment of the FRMPs.

The following area for further development was identified:

- Flood hazard and risk mapping appeared to be ongoing during the first cycle to cover the remaining areas at risk. Conclusions from the finalized mapping should inform the second cycle PFRA, FHRM, and FRMP steps.

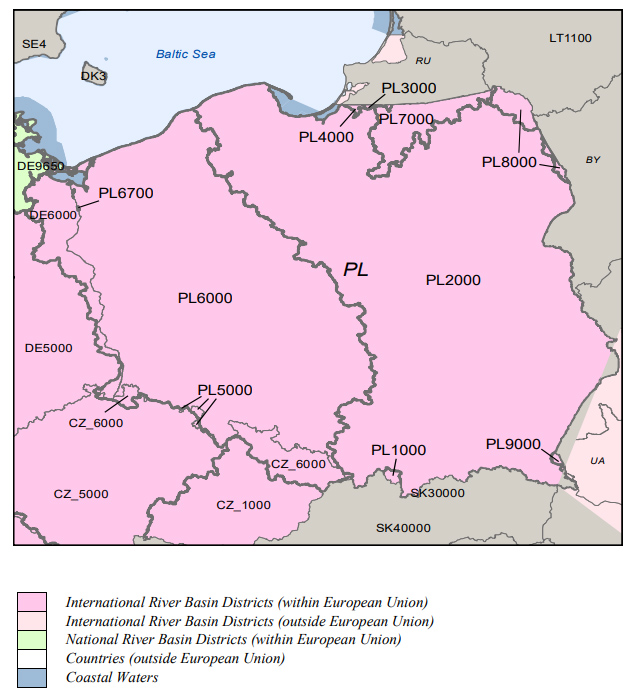

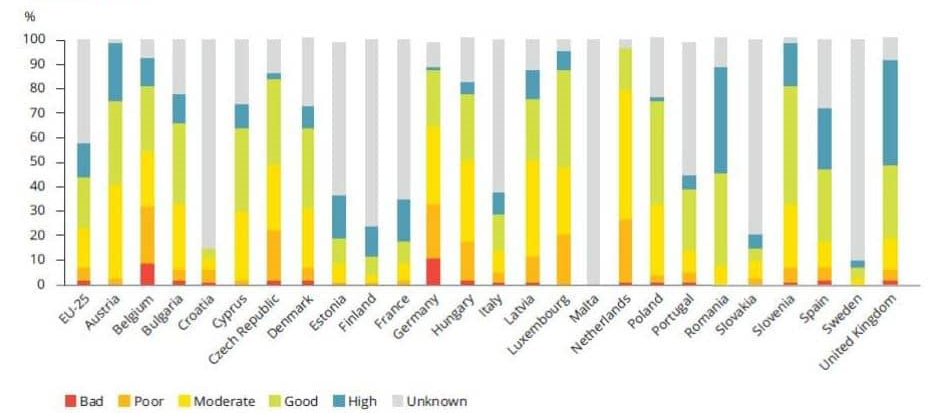

Poland and the Water Framework Directive

The picture below shows the status of surface water bodies in the Member States, where the colors corespond with the quality of it. Poland waters mainly have a moderate to good quality status.

The assessment of groundwater status generally follows a national approach. In Poland 132 (82%) water sources were reported to have good quantitative status and 29 (18%) poor status. The River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) report that the main reason for groundwater bodies not achieving good quantitative status is excessive, long-term consumption of groundwater that exceeds the resources available. A total of 150 (93.2%) out of 161 groundwater bodies were reported to have good chemical status and 11 (6.8%) poor status.

The overarching problem identified in the Polish implementation of the WFD as reflected in the RBMPs is the inconsistency of the planning process. In particular, the fact that there is no integrated approach to water management and there seems to be a disconnection between water management and the environmental objectives of European water legislation. There is also no evidence of an integrated policy approach between water management and other related policy areas such as navigation, energy production, flood protection, agriculture, etc.

Poland and the Nitrates Directive

The implementation program for the Nitrates Directive was prepared in 1999. According to the agreement with the European Commission, the rules of this Directive should have been implemented in Polish legislation by 2002, the vulnerable zones designated by 2003, and the action programs for these zones established by 2004.

The 2017 Water Act introduced a new approach to reducing water pollution caused or induced by nitrates from agricultural sources. It extended the scope of the Nitrates Action Programme (NAP) to address water pollution by nitrates. The regulation applies to all farmers throughout the country. The whole country has been designated a ‘Nitrate Vulnerable Zone’ and the rural development program has increased its support for building manure storage facilities to reduce the risk of nitrates leaching into the water. Extension of the NAP for the reduction of water pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources and prevention of further pollution imposes obligations on all farmers throughout the country. A variable fee for water abstraction for agricultural purposes and for irrigation of land and crops was introduced.