Irish waters decline due to growing dairy industry

-

Fergal MacErlean

Fergal MacErlean

Share article:

Irish waters decline due to growing dairy industry. Fugitive nitrogen losses from intensive agriculture is a key factor in this deterioration which corresponds with a growing dairy herd. Investigative journalists Fergal MacErlean and Cecilia Fasciani researched the relation between intensive dairy agriculture in Europe, with a focus on Ireland and Italy.

This article follows a publication of an article on water pollution due to intensive dairy agriculture in Europe. The second publication is the result of extensive research in Ireland. In June 2023 a report of the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) on Water Quality in Ireland in 2022 showed that nitrogen levels in Irish rivers and groundwater increased between 2021 and 2022. Nitrogen is too high in 40 percent of river sites and in 20 percent of estuarine and coastal water bodies. In addition, phosphorus levels are too high in 28 percent of rivers and 36 percent of lakes.

Dairy industry

The number of dairy cows in Ireland is 1.63 million (of some 7.4 million cattle), showing a rise of approximately 40% over the last decade with artificial fertiliser imports increasing by 35% over a similar timeframe. According to the EPA between 2015 and 2021 dairy cow numbers increased by 22.6% and milk production increased by 36.9%. The industry spread across some 18,000 multigenerational family-owned dairy farms is worth € 13.1 bn a year to the Irish economy, supports 54,000 jobs and saw a record € 6.8 bn in exports in 2022.

Reduction of dairy cows

In May 2023 Ireland’s Agriculture Minister, Charlie McConalogue, said a voluntary dairy reduction scheme was under consideration in a bid to meet greenhouse gas emission cuts in the sector of 25% by 2030. The government would compensate farmers for reducing their herds. The Department of Agriculture analysed the effects of culling 200,000 dairy cows. Irish farmers haven’t formed a political party nor launched high profile protests, as yet, like their Dutch counterparts fighting their country’s planned nitrogen cuts, but tensions are rising as harsher environmental restrictions and increased input costs bite. Stephen Arthur, chairman of the Irish Farmers’ Association dairy committee, has railed against a ‘current anti-dairy farmer narrative’.

Farmers income increases

Despite rising production costs, these farms experienced sharp income increases in 2022, largely due to high milk prices, according to a survey by the state’s research and advisory farming agency Teagasc. That year the average dairy farm saw its income increase by more than € 50,000 on 2021 figures to € 150,000. Some 1.45 family labour units were required to generate this income on the average farm with 93 cows.

Livestock boost

With the abolition of milk quotas in April 2015, and a government campaign to increase the national herd, many farmers took out large loans to boost their livestock numbers. Simultaneously there was an increase in farms benefiting from the derogation from the nitrogen limits constraining the application of manure imposed by the nitrates directive which was first granted in 2007. Essentially this allows for larger herds and higher stocking densities. In effect a farmer must not exceed two dairy cows per hectare without a derogation but can farm at almost three cows per hectare if approved for a derogation. The directive aims to protect water quality across Europe by preventing nitrates from agricultural sources polluting ground and surface waters and by promoting the use of good farming practices.

Derogation benefits

Three Member States continue to benefit from a derogation — on application to the European Commission — that allows them to use, for qualifying regions, up to 250kg of livestock manure nitrogen per hectare rather than the general maximum of 170 kg in addition to a chemical nitrogen allowance. Farmers must apply to their national body for the derogation for the application of the higher fertiliser levels which allows for increased yields from grassland or arable crops in Ireland, Denmark and the Netherlands. The European Commission makes its decision on the basis of objective criteria such as high net precipitation, long growing seasons and high nitrogen uptake by crops or grass.

Nitrates Action Plan

The European Commission granted the latest derogation to Ireland in 2022 for the period up until 2025 but insisted on a two-year review of water quality data instead of the usual four-year one as happened in the Netherlands where the derogation will not be renewed. Ireland’s current Nitrates Action Plan — which delivers the requirements of the Directive — has been controversial. High nitrate levels in water bodies were described as being ‘unsustainable’ in the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the draft Fifth Nitrates Action Plan (NAP) by environmental consultants.

New derogation inadvisable

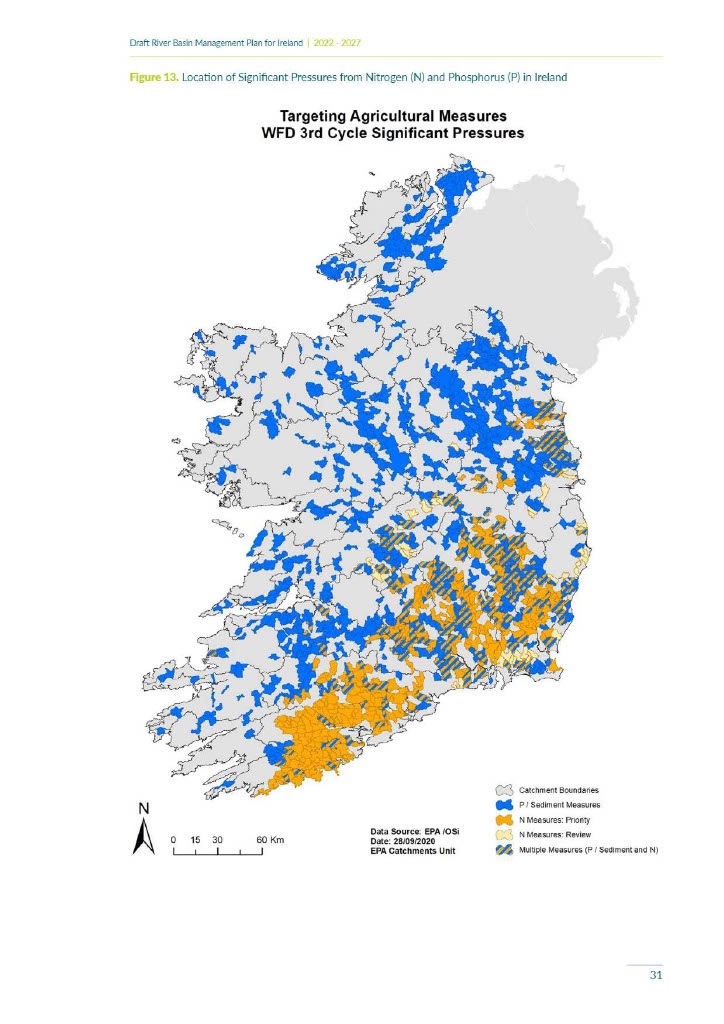

The report by the RPS Group recommended that the Irish government did not apply for another derogation from the EU. “For the state to seek to facilitate even greater nitrogen loading to the environment is environmentally unsustainable and it is recommended that the state does not seek this derogation”, their stark assessment states. The report adds: “The Nitrogen Action Plan measures are failing to protect water quality from agriculture, as required under Article 1 of the Nitrates Directive. This is in part as a result of the industry expansion but poor enforcement and compliance is also hindering progress in implementation. In particular, nitrogen pollution in the south and south-east of the country is damaging the ecological health of many estuaries and nearshore coastal waters. In these areas, which have freely draining soils, nitrate seeps rapidly into groundwater, and losses are closely correlated with the intensiveness of farming. The higher the rate of application of nitrogen, the higher the nitrate concentrations in waters.”

Letter against new derogation

The report’s findings were highlighted in a January 2022 letter to the European Commission’s Land Use and Management Unit by the Irish conservation group An Taisce. This followed a December 2021 meeting when an Irish delegation met with Commission officials to discuss statements made in the Strategic Environmental Assessment which accompanied Ireland’s draft NAP. A 30-page letter from An Taisce to the head of the unit sent in November 2021, requesting the meeting, centred on the reasons why the Commission should not grant Ireland a nitrates derogation. That clearly spelt out the scientific reasoning and boldly states that “by granting an additional derogation, the Commission will be facilitating Ireland to continue to be in breach of the Nitrates Directive and Water Framework Directive obligations, and likely concomitant breaches of the Habitats Directive.”

Water pollution

For example, under the heading ‘Compliance’, the November 2021 letter states: “The draft NAP clearly outlines that Ireland has low levels of compliance with the Good Agriculture Practice for Protection of Waters (GAP) regulations, including the fact that 40% of dairy farms are not compliant with slurry storage requirements to prevent nutrient pollution from watery animal waste.” And the letter highlights how a 2021 EPA report outlined that problem catchments required nitrogen load reductions of more than 50% to achieve estuarine regulatory values for WFD compliance. Yet the final NAP and GAP regulations were for an initial 10% reduction of chemical nitrogen application, which “may be increased to a 15% reduction nationally after the midterm interim review of the programme”. Modelling by Teagasc to inform the draft NAP predicted that spreading 10% less chemical fertiliser mitigated the risk of nitrate loss by just 3%.

National High Court hearing

Ireland’s Fifth Nitrates Action Programme was finalised in March 2022 and the Commission granted the derogation the following month. In the summer of 2022 An Taisce brought legal action against the Irish Government due to levels of nitrate pollution. It is seeking orders quashing the NAP and the setting aside of the Commission’s decision to grant the derogation. An Taisce’s substantive High Court hearing will take place over four days in mid-December. In response to a query as to the lack of action in spite of the warnings, a Commission’s spokesperson said: “Under the Nitrates Directive, Member States are responsible for adopting their national action programmes in line with the applicable national and EU rules. “The Commission does not approve the action programmes and does not issue an opinion on them. But the Commission can initiate infringement proceedings in cases where it considers that a Member State is not in compliance with its obligations under the Directive. There is currently no such case against Ireland. “The Commission is aware of the ongoing legal proceedings before a national court regarding the implementation of the Nitrates Directive in Ireland. The Commission does not comment on such proceedings.”

No derogation after 2026

Powerful lobby groups, such as the Irish Farmers’ Association (IFA), which has an office in Brussels, were naturally relieved when the derogation was granted and their agenda and that of the Irish government was approved. That situation now appears to have changed. On 6 September 2023 the EU Commissioner for the Environment, Virginijus Sinkevičius said that there was no prospect of re-opening the current Commission Decision conferring a derogation from standard Nitrates Directive rules on Ireland. In addition, due to unfavourable water quality results, the derogation limit is due to reduce to 220 kg per hectare at the end of 2023 in certain areas. The Commissioner is expected to visit Ireland on November 2023 to discuss the Nitrates Derogation. A dairy industry expert said Ireland would be preparing to apply for the nitrate exemption in the autumn of 2025. Following the Commissioner’s September announcement IFA members protested outside the Department of Agriculture’s offices on Kildare Street in central Dublin.

WFD Exemptions

But the issue of derogation is just one area which, if not carefully monitored, can undermine the objectives of the Water Framework Directive. The other glaring one is that of exemptions from the Directive. “Exemptions were applied to a large number of water bodies for the second river basin planning cycle (2016-2021), primarily to extend the deadline for achieving the objective from 2015 to 2021 or 2027,” an EPA spokesperson said. Deadline exemptions were in place for 1,426 water bodies of the 1,460 water bodies that were At Risk of not meeting their environmental objectives of the total of 4,829 water bodies. There were a handful of exemptions for less stringent criteria given to water bodies associated with closed mine sites.

Claire Baffert, Senior water Policy Officer at the WWF European Policy Office, said: “Exemptions to the Water Framework Directive are supposed to be limited to exceptional circumstances, but far too often they have become the rule. Member States need to stop using exemptions as the norm. “The WFD also requires Member States to specifically set out the reasons why they apply WFD exemptions in the RBMP and their updates. This is why the Commission is grounded to ask Ireland to state how many of the country’s water bodies Ireland wishes to exempt under that Directive because of agricultural pressures.”

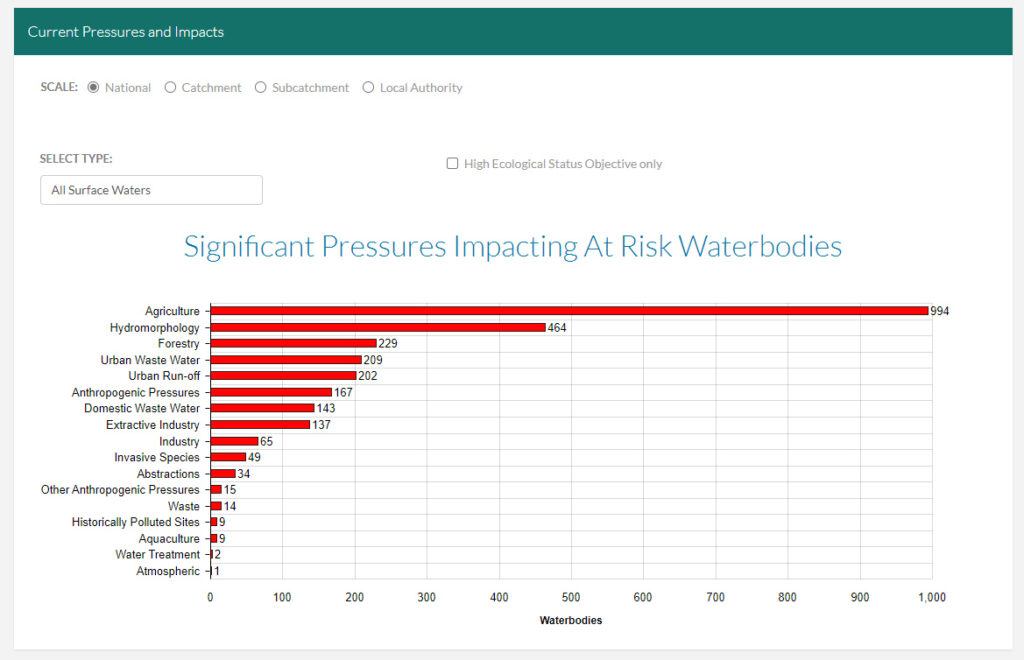

Agriculture as the major polluter

Exemptions for the third, late, River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) were, in late September 2023, still to be reviewed by the relevant Minister. That draft RBMP has identified 1,603 water bodies that are categorised as At Risk of not meeting their environmental objective of good or high-status of a total of 4,842 water bodies. Agriculture is the main significant pressure impacting on 1,000 of these water bodies. The draft RBMP states that: “It is likely that the implementation of measures and the time required for them to take effect will extend beyond the third-cycle (after 2027). Therefore, the use of the exemption provisions [under the WFD] for extended deadlines will be required.”

In March 2022 the European Commission, in a strongly worded observations letter, on Ireland’s draft Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Strategic Plan 2023-27 requested information “on the consistency of the CAP strategic plan with needs and targets arising from the Water Framework Directive – including how many of the country’s water bodies Ireland wishes to exempt from the requirement of reaching ‘good status’ under that directive because of agricultural pressures.” A Department of Agriculture spokesperson said: “On the basis on the Commission’s observation letter, Ireland updated the text in the CAP Strategic Plan (CSP) to better explain how measures outside of the CSP would address water quality.”

Farmers will become victims

Like many of Ireland’s dairy farmers, Kevin Murphy who has a herd of 300 cows on 137 hectares, near Gorey in the south-eastern county of Wexford is angry at the Irish government. He began farming in 1982, a year before milk quotas were introduced which ‘restricted’ his business until 2015 when the system ended. Murphy feels farmers were wrongly encouraged to invest heavily in expanding their herd and land and says they have been given just three months to comply with the new derogation rules affecting more than 3,000 dairy and beef farmers of the 7,000 derogation farms. Some of these will see herd reductions of up to 40% equating to an income drop of almost a third.

Cull cows

Speaking on his farm of lush fields, days after the derogation cut was announced, he said: “The government said we need a 50% increase in production in the five year plan [announced in 2020]. We’ve just about got that and then all of a sudden they say sorry we made a mistake.

“We’ll have to cull some cows. We definitely can’t afford to carry any extra young stock,” said the middle-aged farmer who believes the next generation will not enter the sector as he feels it is not profitable enough.

Improvement takes time

Murphy also feels that the new changes are without a sound basis due to time lags for nutrients to leach through soils to reach water bodies. “I wouldn’t mind if it was based on science. You can’t just change your farming methods today. Test the water tomorrow and it’s going to be different,” he said. On poorly drained soils, depending on rainfall, nitrogen can take four years to leach down through a soil mass into groundwater or a river while phosphorus can take two to three decades. On freely draining soils the nitrogen leaching lag times can be less than a matter of months.

Ireland is unique

“We’re different to anywhere else in Europe. We’re able to grow 14, 15, tonnes of grass a year which they can’t do anywhere else in Europe out in the open with normal conditions.” Until last year Murphy and other derogation farmers were allowed spread a total of 500kg of nitrogen per hectare, with half being manure and half being a chemical supplement. In 2022 a 10% cut to chemical nitrogen allowance across all stocking rates was introduced.

Nitrogen spikes

Murphy cites Teagasc soil scientist David Wall as saying that “500kg of nitrogen per hectare when you’re growing 14, 15, tonnes of grass is a safe limit because the grass is able to use that nitrogen. The problem is that you have to apply the [chemical] nitrogen and the organic nitrogen where the grow is.” The dairy farmer cautions that failure to do so on parts of the farm that are overloaded with nutrients leads to ‘hotspots’ and consequent problems for adjacent water bodies which farmers learnt during the dry summer of 2018 that affected the ability of highly soluble nitrogen to be utilised.

“Farmers didn’t know whether to keep spreading nitrogen or to stop. Any nitrogen that was spread was extra and the grass didn’t grow. We had applied too much nitrogen for what we were able to grow. But when the rain came it stripped all the nitrogen out of the system. And you had your testing in the catchments and there was an awful spike in nitrogen. “The level of nitrogen we’re spreading now is a good bit less than five years ago. And we’re getting the same amount of grass. We’re sowing extra clover [which provides nitrogen to the soil],” Murphy said, adding that GPS is used for precision spreading of fertilizer.

Lack of drainage

Part of his farm is in the Ballycanew catchment, one of six predominantly agricultural drainage areas, that form the 2008-initiated Government-funded Agricultural Catchments Programme (ACP) which is managed by Teagasc. The dominant soils in the lowland of this catchment are surface water gleys, which have poor drainage characteristics and are susceptible to phosphorous loss to waterways during heavy rainfall events through running off the thick soils.

Eddie Burgess, a catchment science specialist on the Agricultural Catchment Programme, said from Murphy’s farm: “The logic of the total application of 500 kg of nitrogen per hectare is that grass has a great ability to take up nitrogen and up to a total application of 500 you haven’t hit the diminishing returns. If you go over 500, if you go up to 550 or 600, the amount of surplus nitrogen that won’t be used increases dramatically.” Talking about the Ballycanew catchment, Burgess said: “The soils have a high clay content. The nitrate levels around here are almost always below the target figure that the EPA are looking for of 2.6 [mg/l] regardless of the stocking limit, regardless of the nitrogen application. Half an hour away [on freely draining soils] no matter what they do nitrogen will always be a problem.”

The evolution of groundwater and stream water quality over time involves a complex interplay between agronomic practices, catchment meteorology, hydrogeology and hydrology. Burgess stressed how soil type, weather, and other aspects influence nitrate loss, such as the crucial timing of applying surplus nitrogen.

Change to green nutrients

“We can do things better,” Burgess said as he outlined how Irish dairy farming could continue to cut chemical nitrogen input, grow more clover and other multi species swards which introduce the nutrient to grass systems. But the catchment science specialist was clear that Irish farming is not currently achieving what was required in meeting the objectives of the Water Framework Directive for 2027. “We’re not making progress nationally.”

And, in 2021, after 13 years of management only of the six ACP sub-catchments reported water quality consistent with WFD mandatory standards. Ballycanew, part of the Owenavorragh catchment which is an important salmon spawning system, had an ecological status of ‘poor to moderate/poor’ and failed the regulatory WFD levels for phosphorous. Burgess said that due to the “same problems that were there when we started, water quality hasn’t changed massively in the catchments programme.”

Urine contamination

One of the intractable problems compounded by an inflated stocking density is that of urine patches. On intensive grassland dairy farms nitrate contamination of water occurs as the amount of nitrogen in a cow urine patch is many times that required for plant growth – the excess either runs off into waterways or leaches through the soil into groundwater. Urine is highly concentrated in urea which has more than 1,000kg of nitrogen per hectare. Modelling by Teagasc to inform policy decisions for the draft NAP found that urine patches led to more than 60% of nitrate loss – more than twice that from artificial fertilizer – and far above the 8% lost from slurry in leaching tests to a depth of one metre. Within an Irish dairy system it has been estimated that 14% of the soil surface was affected by urine at stocking rates of two livestock units.

An Taisce highlighted this as ‘particularly pertinent for derogation farms’ in its November 2021 letter to the Commission. “Derogation farms are obliged to have a suitable land area for spreading slurry, but there are no limitations on the number of livestock units they can have on a single piece of land. There is no calculation of, or controls on, the nitrogen load as a result of direct deposition by the grazing animal while at pasture. There is no requirement to move the animals to another grazing platform or indoors once the nitrogen threshold of 250 kg per hectare has been reached due to direct urine deposition.”

Nitrogen leaching from urine patches can be reduced with more precise nutrient applications, and cuts in the duration of grazing, and stocking rate at times of heightened risk. The final NAP addresses this with a reduction in the amount of crude protein that dairy farmers are allowed in concentrate feedstuff fed to grazing livestock during the summer season. Reducing this has an impact on secreted nitrogen but other than NAP documents stating that this measure will “help mitigate urine patch impact” no figures have been compiled officially.

Protein reduction

Marie Archbold, a Water Scientific Policy Adviser with the lead governmental department for nitrates regulations said: “On crude protein and urine reduction the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage hold no records specifically related to this.” A Teagasc spokesperson said: “The reduction in crude protein levels will impact the nitrogen balance at a farm and cow level. Many previous studies have shown that reducing the nitrogen surplus at a farm level has an impact on nitrogen loss. No modelling took place on this aspect of dairy cow feeding.”

Reduction of nitrogen expected

The Teagasc spokesperson also said that better nitrogen leaching figures were expected. “In the latest Teagasc report published in [February] 2023, the analysis carried out suggests that current changes that are being introduced in the Fifth Nitrate Action Programme coupled with increased ambition in fertiliser nitrogen reductions in the [government’s ten year] Food Vision strategy, would result in a reduction in nitrogen leaching.” Depending on the modeling used this would be between 5.9 kg per hectare and around 9kg per hectare, or 12 to 19%. Reduced stocking rate figures and NAP-introduced changes to fertiliser and slurry spreading dates also impacted the recorded figures.

Criticism

Friends of the Earth (Ireland) director, Oisín Coghlan, has been scathing of the Food Vision 2030 Strategy for the Irish agri-food sector. He said: “This industry-led plan for agriculture is not aligned with our international obligations on climate pollution, biodiversity and water quality.” Elaine McGoff, Head of Advocacy with An Taisce, has stressed the need for rigorous NAP measures in relation to the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP), the management tools for Member States to achieve good water quality with the third cycle for 2022-2027 in preparation.

“The RBMP relies heavily on the measures proposed in the Nitrates Action Programme (NAP) and Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) regulations. Beyond that, the other measures proposed are voluntary, somewhat vague, not time-tabled or targeted. “This is why the reliance on the measures in the NAP is absolutely critical. If they fail, then the largest pressure on water quality will not be adequately addressed. In reality, if they fail, things will get significantly worse,” she told a government committee hearing in 2022.

Inadequate inspections

Disturbingly, the issue of farm inspection for potential water pollution is woefully inadequate: there are just 11 full-time equivalent staff, 16% of what is required. A City and County Managers Association report has advocated a five-fold increase in the number of full-time inspectors.

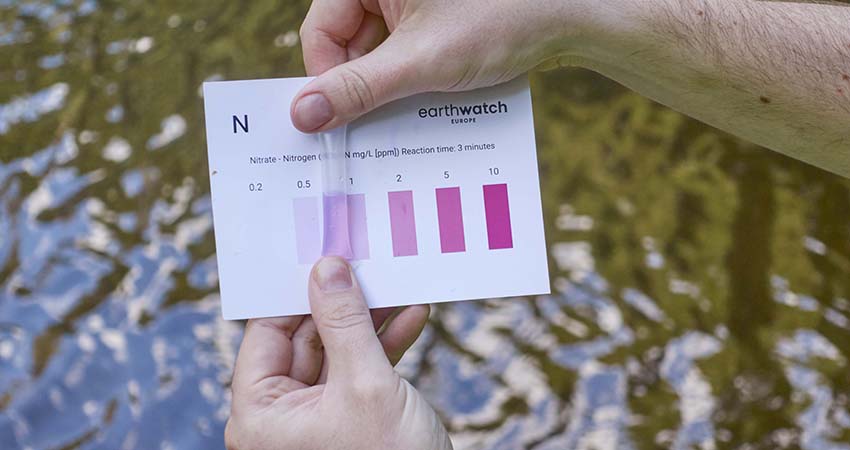

Citizen science

Half an hour’s drive south-east of Gorey, Jonathon Hughes is taking water samples from the River Boro at an idyllic wooded spot. The Sustainable Enniscorthy volunteer is one of a dozen who upload water sample data from the River Slaney and tributaries in their local area. Their work with the Freshwater Slaney project is part of a wider global citizen science project, FreshWater Watch. This aims to empower communities to collect freshwater data and contribute to national Sustainable Development Goal reporting. Ultimately the local group will present their findings to the residents of Enniscorthy as part of their drive to increase awareness of water quality issues. The Sustainable Enniscorthy volunteer said: “Everyone needs to work together. Identify what are the problems and put a solution in place to resolve them.” He added: “Water quality for farming is really important because farmers rely on good water for their crops and their animals. They want good water quality.”

Sustainable Enniscorthy volunteer Jonathon Hughes check water turbidity with a Secchi tube by the River Boro. Photo: Fergal MacErlean.

River Slaney

The Slaney river, which is tidal more than 20km upriver from Wexford Harbour to Enniscorthy, drains almost 2,000km². Its estuary is one of Ireland’s worst impacted for nitrogen exceedances. Of the total waterbodies in the Slaney & Wexford Harbour Catchment, 40% are At Risk of not meeting their Water Framework Directive objectives. These encompass 40% of the groundwater bodies, and 39% of the river waterbodies, including the Lower Slaney Estuary and North Slob Channels.

The significant pressure affecting the greatest number of the Slaney’s waterbodies is agriculture, followed by forestry, and urban waste water, according to the third cycle draft report for the catchment. Hughes who works as a wastewater enforcement inspector with the EPA is well aware that discharges from urban wastewater contribute to excess nitrates and phosphorus in Ireland’s rivers and lakes. He takes sample from the Boro using simple water chemistry testing kits to measure the presence of nitrates and phosphates, and assesses the turbidity among other observations.

Wexford Wildlife Reserve

The Wexford Wildlife Reserve, a Ramsar site, sits on the mudflats of the North Slob Channels which hold 45% of the world’s Greenland White-fronted geese every winter. These 8,500 individuals are among the thousands of wildlife species affected by the changing ecology of the estuary and mudflats owing to excess nutrients. The waterway also has populations of three lampreys – primitive fish species – that are protected, along with spring salmon, freshwater pearl mussels and more than thirty other species, under a Special Area of Conservation that extends from the harbour to the edge of Enniscorthy and includes threatened alluvial forests.

Right measures in the right place

The Sustainable Enniscorthy volunteer said: “The reports are clear, it’s the intensification that’s causing more problems than anything. Something has to give. The EPA have a line `the right measure in the right place’. That’s really what’s needed. If there’s an issue identified and someone goes out and says this is what needs to happen here. Just here, not everywhere, just here. Just this waterbody, or this catchment maybe, but that’s the piece we seem to be missing. What we’re trying to do is go out to people and say this is the story with the Slaney in Enniscorthy and the tributaries and this is what the current stats says and this is what it needs to get to”, Hughes said. Counting several farmers among his friends he is hopeful that the group’s work will engage farmers and encourage rural home owners to clean septic tanks properly.

Dutch conditions

Elaine McGoff warns that we can’t keep doing what we’re doing. We’re breaking European legislation. Farmers should be looking to the government to provide a voluntary buy-out scheme or a credible way forward that protects them economically.” Citing the case of the Netherlands, which has, on average, a higher dairy intensity than Ireland, McGoff said: “Prior to a court case to try to limit nitrogen they were reducing cattle numbers on foot of a phosphate pollution problem. We’re going the same track. They’re further ahead of us. We are getting worse year on year so that is where we are headed to.

Too many cows

“The sheer numbers of cows is what’s driving water quality decreases. When it comes to water quality issues we should be looking at it according to the watershed.” An aspect of the Fifth NAP that had been welcomed by environmentalists is banding where excretion rates are linked to dairy cow milk yield; as higher yielding dairy cows have higher organic output they are confined by tighter stocking limits resulting in the need for additional land or reduced stock numbers.

Catchment limits

McGoff said: “What we’re seeing happening on the ground is there are dairy farmers buying up land from beef farmers and tillage farmers. It might not make that big a difference to water quality because the dairy is expanding all within the same catchment. Really what we need are catchment limits. Instead, what we’re seeing, is not taking the cows out of the problematic watersheds. You really need a science based approach and the data is there. Nitrate pollution depends on rainfall and soil type and slope. The EPA has done modeling and there are some areas of land that could tolerate a higher stocking density and there are other areas that are really vulnerable to leaching so there should be no cows there, or very few cows.”

Unhealthy waters

Almost half (47%) of Irish surface waters were found not capable of sustaining healthy ecosystems in the last major report by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), an independent public body. This environmental degradation was predicted in assessments of Ireland’s planned massive dairy expansion to the agency back in 2008, the then ex-director of the EPA said. “It was known. It is not a surprise or a shock, or it should not be,” Dr Micheál Ó Cinnéide told a government committee hearing in September 2023.

Targeted action is needed

The Water Quality in Ireland Report 2016-2021 highlighted the further decline of water quality and states that, at the current level of progress, Ireland will fail to meet the EU and national goal of restoring all waters to good or better status by 2027. It is believed that Ireland is following the same trajectory as the Netherlands following the massive expansion of its dairy industry. The assessment shows a significant deterioration in the number of estuaries and coastal waters in satisfactory condition, mostly along the southeast and southern seaboards. Urgent and targeted action is required to reduce nitrogen emissions from agriculture in these areas, the EPA states.

Water News Europe is publishing a LONGREAD of European investigative journalists on pressing water issues in various Member States. The first article painted the European picture. The second story concentrates on agricultural pollution in Ireland and the last article will sketch out the situation in Italy.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe